VMP 3.x Virtualization Unpacking – Part 3

0 – ⚠️ IMPORTANT NOTE

This article explain how VMProtect works, not how to crack a VMP protected software. I’m not talking about any kind of Licensing System provided by VMP, or a developped one using VMP. I DON’T SUPPORT PIRACY in any way. This protection (cracked / leaked version of it) is used to protect malwares, and my objective with this article is to improve the commun knowledge of it to help and simplify the analysis of this type of malware. I posted this article ONLY for EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES. This could be maliciously used and it’s why I DO NOT GUARANTEE AND IS RESPONSIBLE, in no case, of such use. You are responsible of your actions towards this article.

I – Intro

Hello, finally, like I said a while ago here is the Part 3 of my work around VMP. A step in the madness of virtualization. I’m not going to talk about specific stuff like Licensing System of VMP, Locked by key virtualized routines and other things that involve comercial stuff. My motivation is the challenge of understanding something that big, and help malware reversers to understand malicious content protected by VMP. My analysis in only based on Windows x86 virtualization, I will analyse VMP routines, and give an example while explaining how hard it is to understand.

Note : I’m not perfect regarding my reverse, I could be wrong in some part

II – Demo vs Paid

Demo version is not even close to the difficulty of paid version. Demo version is a “normal” vm in term of conception, a dispatcher with a switch like offset jump to handles. You can trace easily the vm code, there are no key chain to jump to the next opcode, the opcode arguments are not even ciphered. And there are way less mutations in handles. Files produced by the demo version can’t even be considered as VMP POC as there are less protected than Paid version. Also, keychains where not used for control flow execution in versions 2.x (handle offset was ciphered “statically”), VMP 2.x is basically today’s VMP 3.x demo with rolling key on the operands. In order to do a real research about VMP x86, I based my work on the paid version, thanks to one of my friend that shared a license 🧡

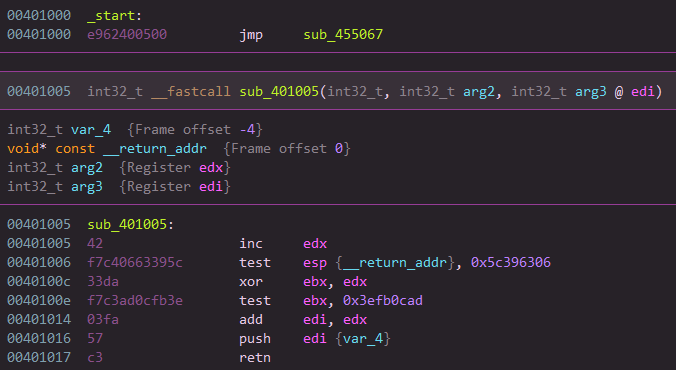

III – First look

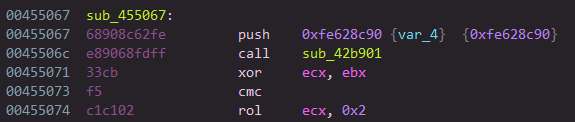

To start somewhere, I will show you what is a VMP routine. The first thing we can notice when we virtualize a function is that a jump to .vmp0 section is made.

And the rest of the original function has been replaced by actual VMP code (in this case it’s an actual handle part)

Then, the code in VMP section is starting by a push uint32 and a call function. Those are the main indicators of a VMP routine. Sometimes it’s a “never returning call” and the data behind it is random, sometimes it’s a custom handle to go to a VENTER.

The pushed value (in this case 0xfe628c90) is the encrypted opcode start (the start VIP, EP), and the called function is a VENTER instruction that will decrypt this value (it’s a small spoil, all is explained below). Let’s pretend that we don’t know it’s an instruction (VENTER). If we continue in the called function, we end up in list of instructions that are obviously mutated (see: Part 2 : Code Mutation), and this code ends on a jump to an address in a register.

If we continue a bit, we start to quickly figure out a pattern. We notice that those kind of “blocks” (code followed by a jump to a register) are executed right after each other. In order to understand, I will split each one of those “blocks” and list them. Here is a preview of the execution flow (each line is the start of a block)

NOTE : I removed parts of junkcode to make things easier

======================================================================

0x7ae901: mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

0x7ae905: lea esi, [esi + 4]

0x7ae914: movzx eax, byte ptr [ebp]

0x83e3c2: lea ebp, [ebp + 1]

0x7d7bf8: mov dword ptr [esp + eax], ecx

...

0x8429bf: add edi, ecx

0x6d015e: jmp edi

======================================================================

0x755912: mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

0x75591a: lea esi, [esi + 4]

0x755925: movzx eax, byte ptr [ebp]

0x6c94c6: mov dword ptr [esp + eax], ecx

0x6c94d7: lea ebp, [ebp + 4]

...

0x79cdbd: add edi, ecx

0x79cdbf: push edi

0x79cdc0: ret

======================================================================

0x7b821a: mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

0x7b8222: lea esi, [esi + 4]

0x7b822b: movzx eax, byte ptr [ebp]

0x7b695c: mov dword ptr [esp + eax], ecx

0x7b6966: lea ebp, [ebp + 4]

...

0x7637cb: add edi, ecx

0x78cc6a: jmp edi

It’s definitly looking like instructions !

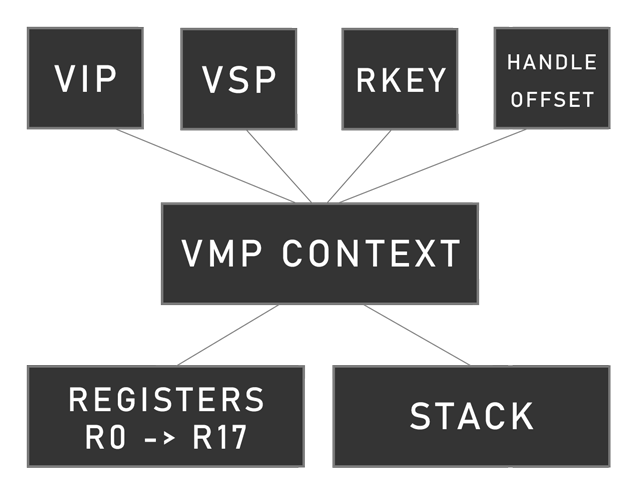

IV – Let’s reverse

So, let’s understand one of those blocks as an example. As you may guess, those blocks are in fact VM instructions (handles).

Here is an example of a raw handle (with code mutation) :

0x45bf82: lea esi, [esi - 1]

0x45bf88: shl dl, cl

0x45bf8a: shr dh, cl

0x45bf8c: movzx eax, byte ptr [esi]

0x45bf8f: inc ecx

0x45bf90: shrd ecx, ebx, 0x3f

0x45bf94: xor al, bl

0x45bf96: rcl cx, cl

0x45bf99: ror al, 1

0x45bf9b: jmp 0x40a4fa

0x40a4fa: dec al

0x40a4fc: xchg dh, dh

0x40a4fe: cmovs dx, ax

0x40a502: bswap dx

0x40a505: not al

0x40a507: dec al

0x40a509: cmp dl, ch

0x40a50b: bsr cx, si

0x40a50f: btc cx, 0x1f

0x40a514: xor bl, al

0x40a516: cmovp dx, bp

0x40a51a: movzx dx, byte ptr [esp + eax]

0x40a51f: sub ebp, 2

0x40a525: movsx cx, ch

0x40a529: mov word ptr [ebp], dx

0x40a52e: sar cl, 0xf6

0x40a531: lea esi, [esi - 4]

0x40a537: mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

0x40a539: test si, 0x701e

0x40a53e: xor ecx, ebx

0x40a540: jmp 0x438108

0x438108: sub ecx, 0x5eac74dd

0x43810e: cmc

0x43810f: not ecx

0x438111: jmp 0x41743d

0x41743d: bswap ecx

0x41743f: rol ecx, 1

0x417441: jmp 0x4513d8

0x4513d8: neg ecx

0x4513da: stc

0x4513db: xor ebx, ecx

0x4513dd: cmp bx, ax

0x4513e0: add edi, ecx

0x4513e2: jmp 0x45af97

0x45af97: jmp 0x4752b4

0x4752b4: lea ecx, [esp + 0x60]

0x4752b8: test sp, sp

0x4752bb: cmp ebp, ecx

0x4752bd: jmp 0x48a866

0x48a866: ja 0x461417

0x461417: push edi

0x461418: ret

As you can see the code mutation is pretty heavy, so let’s remove it. Here is the same version, without junkcode :

0x45bf82: lea esi, [esi - 1]

0x45bf8c: movzx eax, byte ptr [esi]

0x45bf94: xor al, bl

0x45bf99: ror al, 1

0x40a4fa: dec al

0x40a505: not al

0x40a507: dec al

0x40a514: xor bl, al

0x40a51a: movzx dx, byte ptr [esp + eax]

0x40a51f: sub ebp, 2

0x40a529: mov word ptr [ebp], dx

0x40a531: lea esi, [esi - 4]

0x40a537: mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

0x40a53e: xor ecx, ebx

0x438108: sub ecx, 0x5eac74dd

0x43810e: cmc

0x43810f: not ecx

0x41743d: bswap ecx

0x41743f: rol ecx, 1

0x4513d8: neg ecx

0x4513da: stc

0x4513db: xor ebx, ecx

0x4513e0: add edi, ecx

0x4752b4: lea ecx, [esp + 0x60]

0x461417: push edi

0x461418: ret

Ok, now let’s figure out what it does :

0x45bf82: VUNKNOWN: (VIP = esi, VSP = ebp)

# update VIP to point on operand (current VIP is pointing on opcode offset)

0x45bf82: lea esi, [esi - 1]

# get the ciphered operand (1 byte)

0x45bf8c: movzx eax, byte ptr [esi]

# mutated operand decryption (keychain)

# NOTE : ebx contain the rolling key

0x45bf94: xor al, bl

0x45bf99: ror al, 1

0x40a4fa: dec al

0x40a505: not al

0x40a507: dec al

0x40a514: xor bl, al

# push a value into vm stack from vm context

# eax = 8; VCTX[8] -> [VSP-2] = VPUSH R8

0x40a51a: movzx dx, byte ptr [esp + eax]

0x40a51f: sub ebp, 2

0x40a529: mov word ptr [ebp], dx

# update VIP to the next ciphered opcode offset

0x40a531: lea esi, [esi - 4]

# get next ciphered opcode offset

0x40a537: mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

# mutated next handle offset decryption routine (keychain)

# NOTE : ebx contain the rolling key

0x40a53e: xor ecx, ebx

0x438108: sub ecx, 0x5eac74dd

0x43810e: cmc

0x43810f: not ecx

0x41743d: bswap ecx

0x41743f: rol ecx, 1

0x4513d8: neg ecx

0x4513da: stc

0x4513db: xor ebx, ecx

# update absolute handle position with the next handle offset

0x4513e0: add edi, ecx

# reset the next rolling key operand

0x4752b4: lea ecx, [esp + 0x60]

# jump to the next handle

0x461417: push edi

0x461418: ret

So, this handle is a VPUSH16 [VCTX + *] instruction !

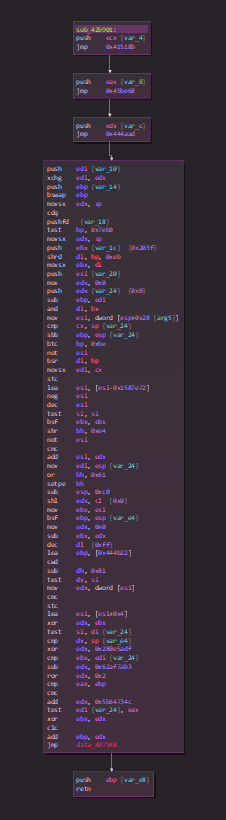

V – VM Structure

Now that we have an idea of what is an handle, here is the VM structure.

V.1 – Architecture

The VM works as follow :

It uses a Virtual Instruction Pointer VIP stored in a x86 register, and a Virtual Stack Pointer VSP also stored in a x86 register. In each VMP routines, those are stored in random registers unlike VMP 2.X, and could be swapped if the routine perform a jump (see parts below).

The VM comes with a context VCTX, in it, there are 18 registers R0 -> R17, and a stack. This context also contain a rolling key operand in esp + 0x60, and the rolling key itself is stored in a random x86 register. In general, an handle offset (handle base address + instruction offset) is stored in a register.

NOTE : if you enable VMProtect’s packer, .vmp1 contain VMP handles and mutated code. Otherwise, all is in .vmp0.

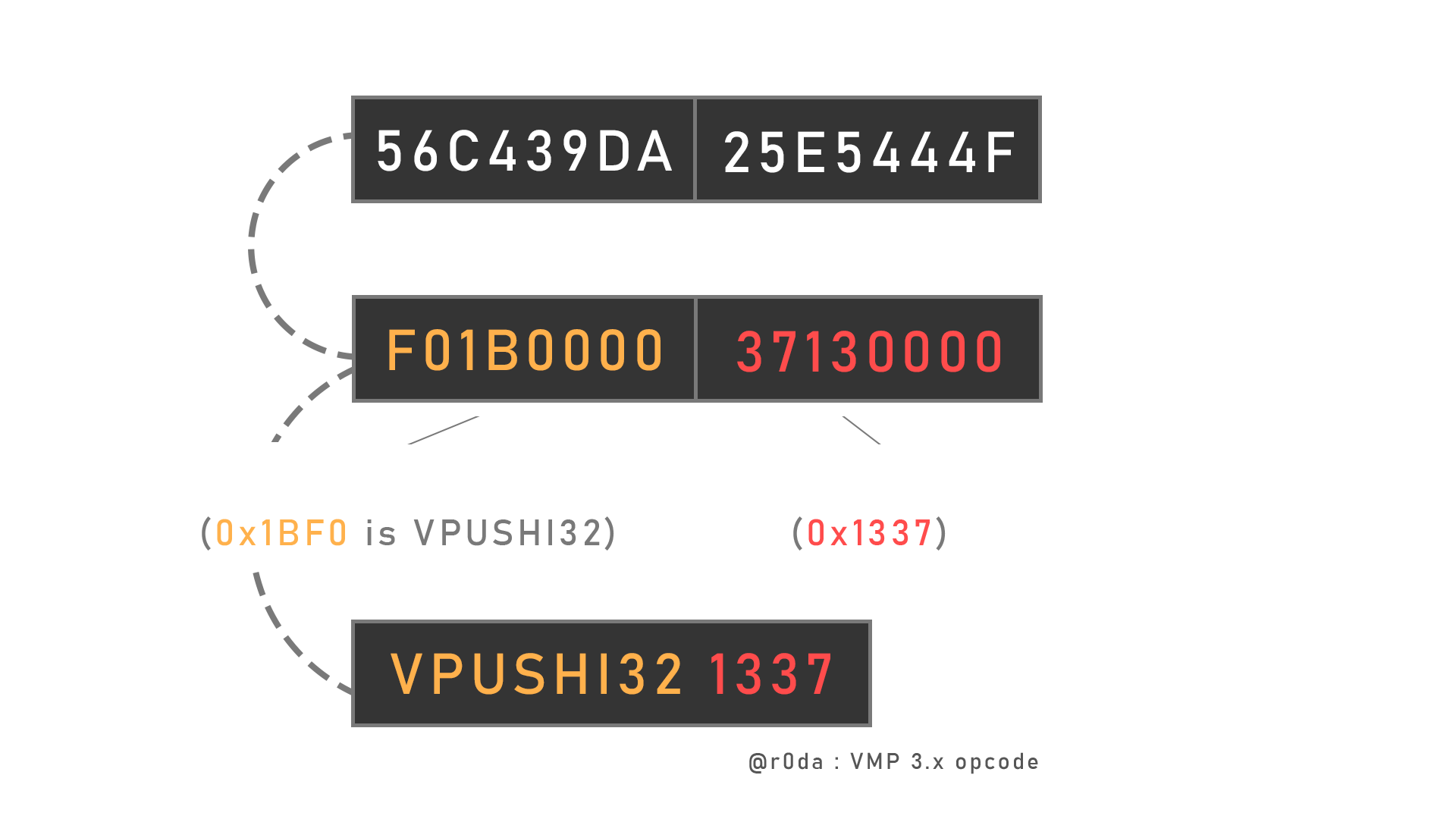

V.2 – Instructions

The instruction set is about ~20 instructions, ~40 if you take in account the variable size (it could be some remaining instructions I haven’t reversed), an instruction is made of two parts, an encrypted handle offset, and its encrypted arguments (operands) (each handle is heavilly mutated)

I will not explain intructions in details, but here are some you can find :

VENTER, VEXIT, VADDU*, VNANDU*, VNORU*, VPUSHV, VPOPR, VPOPVSP, VPUSHVSP, VPUSHI*

VFETCH*, VJUMP_*, VMOV*, VSHLU*, VSHRU*, VMULU*, VDIVU*, ....

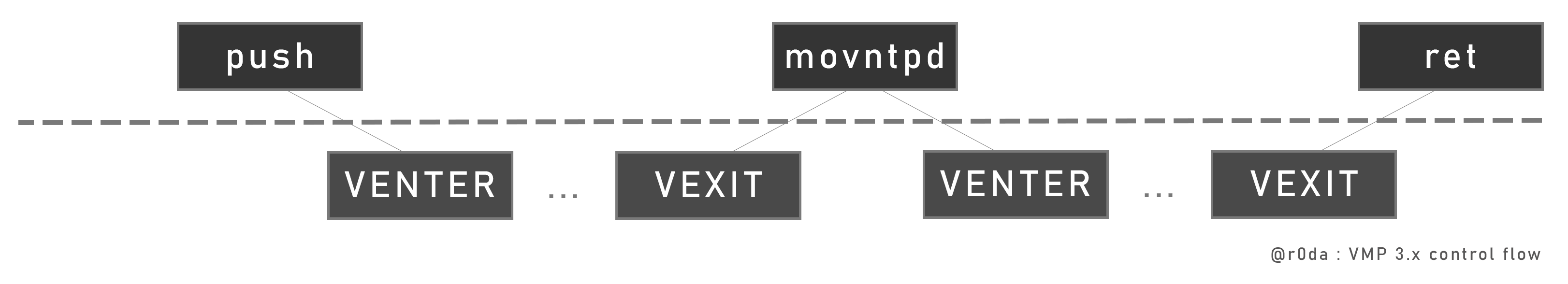

A VMP routine starts by a VENTER intruction, and ends by a VEXIT instruction. When VMP can’t handle the original x86 instruction, it is saved as it is in the VM routine, but it uses VMP’s registers (see: V.4 - Control flow).

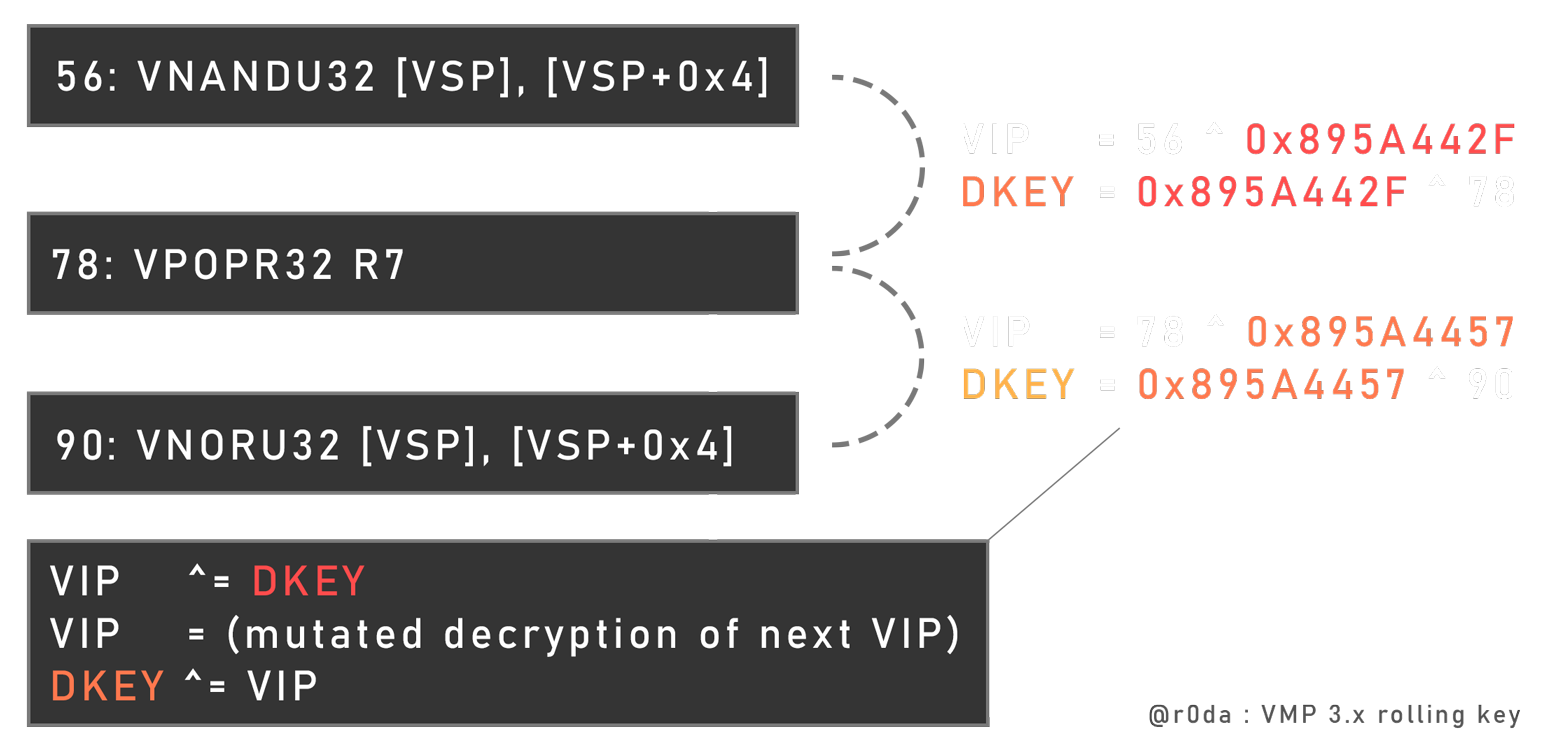

V.3 – Rolling key

V.3.1 – Instruction flow

VMP changed a lot since 2.x regarding this, before, the opcode was grabbed using a simple index in an array, with a jmp right after to go to the handle in function of the opcode in the array. Note that this is still the current behavior of VMP Demo version. Currently, the handle table is still there, but the flow is not “linear” anymore (an index through an array).

Let’s take an example, the current instruction decrypts the next opcode offset (next instruction) with an unique “rolling” key and a unique mutated decryption routine. Rolling means a keychain, like for example the first handle decipher the first opcode with its unique key in edi. During the decryption routine, the key in edi has been mutated uniquely in function of the decryption routine, to allows the next handle to be able to decipher the next opcode.

This means first that you can’t decrypt the opcode flow staticaly without using symbolic execution (like NoVmp with VTIL), and you are also obligated to cross all handles in order to get the opcode. But this also means that you can’t modify the execution flow (or it’s very hard), because if you want to tweak the execution of an instruction, you have make its decryption key feet to the all keychain (static modification).

This is an example of VIP update at the end of an handle :

# VIP += 4

lea ebp, [ebp + 4]

# ebx = last key of the keychain

xor edx, ebx

# mutated decryption routine

inc edx

add edx, 0x49951f73

add edx, 0x794f4349

neg edx

inc edx

# cipher the current decryption key for the next

# handle decryption routine

xor ebx, edx

# current handle + offset

add esi, edx

# jump to next handle

push esi

ret

In this case, the rolling key operand is the handle offset of the previous handle (stored temporary in edx in this example), and the rolling key is stored in ebx.

NOTE : VMP 3.x x64 in the other hand still keep the handle table in a register, and the decrypted handle offset is just added to it, unlike here where the handle offset is increased

V.3.2 – Operands

Like in VMP 2.x, the rolling key is also applied to intruction operand decryption. Unlike V.3.1 - Instruction flow decryption routine, the rolling key operand is the encrypted instruction argument, but the rolling key is the same as V.3.1 - Instruction flow.

# esi = VIP

# ecx = instruction argument

mov ecx, dword ptr [esi]

# update VIP

lea esi, [esi + 4]

# decryption routine with instruction argument as rolling key operand

# ebx = rolling key

xor ecx, ebx

dec ecx

neg ecx

xor ecx, 0x611a1565

cmp ebp, edx

xor ebx, ecx

V.4 – Control flow

So, like mentined above, the instruction flow is made by rolling key decryption (see: V.3.1 - Instruction flow) and a VMP routine start by a VENTER. But, virtualization can’t handle each x86 instructions like I said in an older post, so VMP keep those instructions in the code. At some point during the routine execution, the VM will do a VEXIT to return in x86 context and execute the unsupported instruction. And right after, a VENTER is executed to return in VM context.

Here are some unsupported instructions : MOVDQ2Q, STOS*, FSINCOS, WBINVD, WRMSR, UD2 (of course), MOVNTPD, CPUID ...

This skip is also applied to some loops (see the integrity check of VMP as a good example).

API call are also done outside of VMP. Before the call, a custom VEXIT will pop the arguments in the real x86 context. And right after, the real call is performed using its calling convention.

In rare cases, I saw a VMP instruction that contain custom code, like a loop or a special instruction, without a VEXIT. But it’s not presistant enough so I can talk about it more.

V.5 – About the junkcode

Now that we know the behaviour of VMP, we can consider this to remove more junkcode. So, VMP doesn’t do any cmp / test on VIP and VSP registers as comparisons are melted using MBA (see below). Some instructions are useless, like mov, cmp and xchg on the same register, and some register size are not used in some circumstances (a mov al, dl is not related to a handle that move 32 bits values). If you want more informations about the code mutation engine of VMP, and its junkcode, check my last article on it (Part 2 : Code Mutation).

VI – Automation

So, how to handle this ? You have two main options, doing devirtualization, or tracing the executed VMP opcode. Tracing is simple, as you only have to monitor or emulate each executed instruction, and do pattern matching to see what VMP instructions are executed. Devirtualization in the other hand give you the ability to retrive an x86 code that is close to the original code directly. But it needs some work as you have to understand and reconstruct the control flow in anycase possible, and using an IR to lift and simplify the obfuscated code. Those two options could be done staticaly or dynamicly, this first required emulation to bypass the rolling decryption routines, and the second one needs a framework to handle each aspect of the VM (Triton, Miasm, ..). I shortly detailed the devirtualization approach in IX - Devirtualization.

As I don’t want to spend too much time on this, I made a short tracer based on qiling (using unicorn emulation). This “debugger” will emulate routines instructions, and using pattern matching, will understand which VMP instruction is executed (without handling each control flow).

VII – An example

Now, as we can read the instructions executed by VMP, we can try to understand the code in the VM. Here are two examples of virtualized routines, the first is just a simple math operation around a variable, and the second is an if statement.

NOTE : Of course, this ISN’T the right way to crack VMP, it’s just to show the VM internals.

NOTE 2 : My tracer skipped the decryption routines stuff, all immediates are already decrypted.

VII.1 – Simple routine

In order to understand how a virtualized routine look like, here is an example of a simple code.

Here is the original code :

int var_0 = 0x1337;

var_0 ^= 0x50;

var_0 *= 2;

var_0 -= 5;

var_0 += 0x80;

return var_0;

Here is the original assembly code :

NOTE : as you can see, this code is not optimized due to the constant assignation. It’s intended to see how VMP stores this variables.

mov dword [ebp-0x4], 0x1337

mov eax, dword [ebp-0x4]

xor eax, 0x50 {0x1367}

mov dword [ebp-0x4], eax {0x1367}

mov eax, dword [ebp-0x4]

shl eax, 0x1 {0x26ce}

mov dword [ebp-0x4], eax {0x26ce}

mov eax, dword [ebp-0x4]

sub eax, 0x5 {0x26c9}

mov dword [ebp-0x4], eax {0x26c9}

mov eax, dword [ebp-0x4]

add eax, 0x80 {0x2749}

mov dword [ebp-0x4], eax {0x2749}

mov eax, dword [ebp-0x4] {0x2749}

jmp 0x401043

401043: # NOTE : this will not be virtualized

leave

retn

After virtualization, the code is about 126 VMP instructions.

The first thing executed in the VM is storing the x86 context in VMP registers (VENTER pushed each registers on CPU stack)

0x44378a: VENTER (VIP = ebp, VSP = esi)

0x44faee: VPOPR32 R7 (0x0 -> R7)

0x4771b8: VPOPR32 R9 (0x0 -> R9)

0x41e851: VPOPR32 R5 (0xffffcfac -> R5)

0x4307c5: VPOPR32 R2 (0x503cee8 -> R2)

0x42861f: VPOPR32 R12 (0x0 -> R12)

0x42ac89: VPOPR32 R4 (0x44 -> R4)

0x43de1a: VPOPR32 R15 (0x0 -> R15)

0x481993: VPOPR32 R11 (0x503cf18 -> R11)

0x46ecaf: VPOPR32 R0 (0xffffe000 -> R0)

0x434480: VPOPR32 R6 (0x41c63d -> R6)

0x4045f1: VPOPR32 R3 (0xc046bf9b -> R3)

This code is : int var_0 = 0x1337;

# push current stack pointer

0x462495: VPUSHVSP

# setup the variable 'var_0' at 0xffffcfa8

# (0x4 + 0xffffcfa4) : 0xffffcfa8 -> VSP

0x488c75: VPUSHI32 0x4 (VSP -= 4)

0x46769d: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x4 + 0xffffcfa4 = 0xffffcfa8)

0x44faee: VPOPR32 R10 (0x80 -> R10)

# return to the old stack pointer

0x42cbcb: VPOPVSP

# push two values, those two combined give the variable offset 0xffffcfa8

# 0xfffffffc is an offset to recover 'var_0' after the 'VPOPVSP'

# like after a call, but the 'VPUSHVSP' seems usless in this case

# so it's maybe an obfuscated way get the stack offset of a variable

0x453bd6: VPUSH32 [0x7fffff99] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x43ad59: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

# get the '0x1337' value

0x4472f7: VPUSHI32 0x1337 (VSP -= 4)

# 'var_0' = 0xffffcfa8 = (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac)

# 'var_0' -> [VSP]

0x408a8b: VPUSH32 R0 (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x437891: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x45343d: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

# NOTE : after each VADDU32, a VPOPR32 will pop an additional value pushed by VADDU32

# I still don't know if this VPOPR32 means something

0x4771b8: VPOPR32 R10 (0x91 -> R10)

# 'var_0' initialized with '0x1337'

0x443f3d: VMOV32 [0xffffcfa8], [VSP+0x4] (0x1337 -> [0xffffcfa8])

This code is : var_0 ^= 0x50;

This one is interesting because it uses MBA (see: Defeating MBA-based Obfuscation)

Original : 0x1337 ^ 0x50 = 0x1367

VMP : ~(~(0x1337) & ~(0x50)) & ~(~(~(0x1337)) & ~(~(0x50))) = 0x1367

Here is the code :

# keep 'var_0' on stack top

0x46fd4b: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x41e851: VPOPR32 R3 (0x91 -> R3)

0x44e6d5: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa8] = 0x1337 -> [VSP])

# 0x1337 -> R8

0x4307c5: VPOPR32 R8 (0x1337 -> R8)

# ~(0x50) -> [VSP]

0x453285: VPUSHI32 0xffffffaf (VSP -= 4)

# push the value twice

0x46850b: VPUSH32 [0xffff850b] (0x1337 -> [VSP])

0x4124e2: VPUSH32 [0x20000000] (0x1337 -> [VSP])

# ~(0x1337) -> [VSP]

0x42af58: VNORU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xffffecc8 | 0xffffecc8 = 0xffffecc8 -> [VSP])

0x42861f: VPOPR32 R14 (0x80 -> R14)

# ~(~(0x1337)) & ~(~(0x50)) = 0x10 -> [VSP]

0x45567d: VNANDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x1337 & 0x50 = 0x10 -> [VSP])

0x42ac89: VPOPR32 R10 (0x0 -> R10)

# 0x50 -> [VSP]

0x4545a2: VPUSHI32 0x50 (VSP -= 4)

# 0x1337 -> [VSP]

0x466ec1: VPUSH32 R8 (0x1337 -> [VSP])

# ~(0x1337) & ~(0x50) = 0xffffec88 -> [VSP]

0x48bfe1: VNANDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xffffecc8 & 0xffffffaf = 0xffffec88 -> [VSP])

0x43de1a: VPOPR32 R6 (0x84 -> R6)

# ~(0xffffec88) & ~(0x10) = 0x1367 -> [VSP]

0x420812: VNANDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x1377 & 0xffffffef = 0x1367 -> [VSP])

0x481993: VPOPR32 R1 (0x0 -> R1)

# result : ~(~(0x1337) & ~(0x50)) & ~(~(~(0x1337)) & ~(~(0x50))) = 0x1367 -> [VSP]

# 0x1367 -> R10

0x46ecaf: VPOPR32 R10 (0x1367 -> R10)

0x432c3c: VPUSH32 [0x2c3c] (0x1367 -> [VSP])

# 'var_0' -> [VSP]

0x47231a: VPUSH32 [0x1439] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x472a7c: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x451c9f: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x434480: VPOPR32 R14 (0x91 -> R14)

# 0x1367 -> 'var_0'

0x428820: VMOV32 [0xffffcfa8], [VSP+0x4] (0x1367 -> [0xffffcfa8])

This code is : var_0 *= 2;

# push 'var_0' on VMP stack

0x46835a: VPUSH32 R0 (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x4862b9: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x424828: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x4045f1: VPOPR32 R12 (0x91 -> R12)

0x421e74: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa8] = 0x1367 -> [VSP])

# 0x1367 -> R12

0x44faee: VPOPR32 R12 (0x1367 -> R12)

# push 0x1367 and 1

0x4382b0: VPUSHI8 0x1 (VSP -= 2)

0x406aef: VPUSH32 R12 (0x1367 -> [VSP])

# 0x1367 << 0x1 = 0x1367 * 2 = 0x26ce -> [VSP]

# 0x26ce -> R10

0x40d36f: VSHLU8 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x1367 << 0x1 = 0x26ce -> [VSP])

0x4771b8: VPOPR32 R1 (0x0 -> R1)

0x41e851: VPOPR32 R10 (0x26ce -> R10)

# I don't know x)

0x461c9d: VPUSH32 [0xffff002b] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x45858d: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x4469c9: VPUSH32 [0x61740000] (0x26ce -> [VSP])

# 'var_0' -> [VSP]

0x453bd6: VPUSH32 [0x7fffff99] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x45c02b: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x4770ad: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x4307c5: VPOPR32 R12 (0x91 -> R12)

# '0x26ce' -> 'var_0'

0x40d6da: VMOV32 [0xffffcfa8], [VSP+0x4] (0x26ce -> [0xffffcfa8])

This code is : var_0 -= 5;

Original : 0x26ce - 5 = 0x26c9

VMP : ~(~(0x26ce) + 5) = 0x26c9

Here is the code :

# push 'var_0' on VMP stack

0x4079da: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x42861f: VPOPR32 R3 (0x91 -> R3)

0x43d21b: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa8] = 0x26ce -> [VSP])

# 0x26ce -> R14

0x42ac89: VPOPR32 R14 (0x26ce -> R14)

# push 5

0x45b846: VPUSHI32 0x5 (VSP -= 4)

# push 0x26ce twice

0x408a8b: VPUSH32 R0 (0x26ce -> [VSP])

0x46850b: VPUSH32 [0xffff850b] (0x26ce -> [VSP])

# ~(0x26ce) -> [VSP]

0x40ac1f: VNORU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xffffd931 | 0xffffd931 = 0xffffd931 -> [VSP])

0x43de1a: VPOPR32 R8 (0x80 -> R8)

# ~(0x26ce) + 5 = 0xffffd936 -> [VSP]

0x431c78: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xffffd931 + 0x5 = 0xffffd936)

0x481993: VPOPR32 R12 (0x84 -> R12)

# get stack top

0x470c06: VPUSHVSP

0x47d211: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa4] -> [VSP])

# ~(~(0x26ce) + 5) -> R10

0x45794d: VNORU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x26c9 | 0x26c9 = 0x26c9 -> [VSP])

0x46ecaf: VPOPR32 R1 (0x4 -> R1)

0x434480: VPOPR32 R10 (0x26c9 -> R10)

# maybe to be use later

0x4124e2: VPUSH32 [0x14000000] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x488c75: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

# push 0x26c9 to be stored at 0x46af11

0x466ec1: VPUSH32 R10 (0x26c9 -> [VSP])

# 'var_0' -> [VSP]

0x432c3c: VPUSH32 [0x2c3c] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x43ad59: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x453e4c: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x4045f1: VPOPR32 R6 (0x91 -> R6)

# save '0x26c9' in 'var_0'

0x46af11: VMOV32 [0xffffcfa8], [VSP+0x4] (0x26c9 -> [0xffffcfa8])

This code is : var_0 += 0x80;

# push 'var_0' on VMP stack

# 0x26c9 -> R14

0x47af9a: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x44faee: VPOPR32 R6 (0x91 -> R6)

0x479e60: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa8] = 0x26c9 -> [VSP])

0x4771b8: VPOPR32 R14 (0x26c9 -> R14)

# 0x26c9 + 0x80 = 0x2749 -> [VSP]

# 0x2749 -> R6

0x4472f7: VPUSHI32 0x80 (VSP -= 4)

0x47231a: VPUSH32 [0x145d] (0x26c9 -> [VSP])

0x43e04a: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x26c9 + 0x80 = 0x2749)

0x41e851: VPOPR32 R8 (0x0 -> R8)

0x4307c5: VPOPR32 R6 (0x2749 -> R6)

# 'var_0' -> [VSP]

0x46835a: VPUSH32 R0 (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x437891: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x46769d: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

# push result to save it latter at 0x45cd94

0x406aef: VPUSH32 R6 (0x2749 -> [VSP])

# 'var_0' -> [VSP]

0x461c9d: VPUSH32 [0xffff002b] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x453285: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x45343d: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x42861f: VPOPR32 R14 (0x91 -> R14)

# '0x2749' -> 'var_0'

0x45cd94: VMOV32 [0xffffcfa8], [VSP+0x4] (0x2749 -> [0xffffcfa8])

0x42ac89: VPOPR32 R12 (0x91 -> R12)

# 'var_0' -> R10

0x4112dd: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa8] = 0x2749 -> [VSP])

0x43de1a: VPOPR32 R10 (0x2749 -> R10)

At the end, the virtualized routine return address is pushed (0x401043, the address of leave; retn). The modified CPU context is restored by pushing each value on VMP stack, and VEXIT will set each CPU registers in function of VMP stack.

# push return address

# 0x401043 -> [VSP]

0x4545a2: VPUSHI32 0x401043 (VSP -= 4)

# add offset to return address (used in loops)

# 0x0 + 0x401043 -> [VSP]

0x4469c9: VPUSH32 [0x61740000] (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x46fd4b: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x0 + 0x401043 = 0x401043)

0x481993: VPOPR32 R6 (0x0 -> R6)

# push VMP context

0x453bd6: VPUSH32 [0x7fff0000] (0xffffe000 -> [VSP])

0x408a8b: VPUSH32 R0 (0x503cf18 -> [VSP])

0x46850b: VPUSH32 [0xffff850b] (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x4124e2: VPUSH32 [0x20000000] (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x466ec1: VPUSH32 R10 (0x2749 -> [VSP])

0x432c3c: VPUSH32 [0x2c3c] (0x503cee8 -> [VSP])

0x47231a: VPUSH32 [0x1439] (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x46835a: VPUSH32 R0 (0x0 -> [VSP])

# save the VMP context to x86 registers

0x433bfa: VEXIT

Still here ? As you can see, we can recover the code, but it’s not that easy 🙂

Here is a pseudo code :

int var_0 = 0x1337;

var_0 = ~(~(var_0) & ~(0x50)) & ~(~(~(var_0)) & ~(~(0x50)));

var_0 *= 2;

var_0 = ~(~(var_0) + 5);

var_0 += 0x80;

return var_0;

VII.2 – Virtualized control flow

Now how VMP deal with the control flow, here a simple if state :

int var_0 = 999;

if (var_0 == 999) {

var_0 = 666;

}

else {

var_0 = 777;

}

Its assembly code :

mov dword [ebp-0x4 {var_0}], 0x3e7

cmp dword [ebp-0x4 {var_0}], 0x3e7

jne 0x401025 {0x0}

mov dword [ebp-0x4 {var_0}], 0x29a

jmp 0x40102c

mov dword [ebp-0x4 {var_0}], 0x309

mov eax, 0x539

jmp 0x401039

leave {__saved_ebp}

retn {__return_addr}

Now the virtualized code :

Note : the MBA is too heavy in this part, so I summerized

# MBA to get 0x3e7 (999) .....

# the wanted value is stored in an obfuscated value

# value_1 = [0xffffcfa0] = 0xfffffc18 + 0x3e7 = 0xffffffff

0x45e8b9: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffc18 + 0x3e7 = 0xffffffff)

0x464561: VPOPR32 R13 (0x84 -> R13)

# .....

# a lot of MBA to obscure the comparison

# .....

# push the next jump offset (var_0 = 666;)

0x45d42b: VPUSHI32 0x4522ae (VSP -= 4)

# MBA to produce the obscured compared value

# value_2 = (~0x0 | ~(~(~(~0x0 & ~0x0) | ~0x4522ae) & ~(var_0_obscured))) = 0xffffffff

0x456732: VPUSH32 R13 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x442df0: VPUSH32 R13 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x42ad4c: VNANDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (~0x0 & ~0x0 = 0xffffffff & 0xffffffff = 0xffffffff -> [VSP])

0x4346f1: VPOPR32 R7 (0x84 -> R7)

0x4701ca: VNORU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (~0xffffffff | ~0x4522ae = 0x0 | 0xffbadd51 = 0xffbadd51 -> [VSP])

0x40c7e3: VPOPR32 R7 (0x80 -> R7)

0x47fbe5: VPUSHVSP

# var_0_obscured = [0xffffcfa4]

0x46cda0: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa4] = 0xffbadd51 -> [VSP])

0x45a3d0: VNANDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (~0xffbadd51 & ~0xffbadd51 = 0x4522ae & 0x4522ae = 0x4522ae -> [VSP])

0x474a78: VPOPR32 R2 (0x0 -> R2)

0x416aff: VPUSHI32 0x45221c (VSP -= 4)

0x47c4dc: VPUSH32 R13 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x45e44b: VNORU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (~0x0 | ~0x45221c = 0xffffffff | 0xffbadde3 = 0xffffffff -> [VSP])

0x450d42: VPOPR32 R1 (0x84 -> R1)

0x430a33: VPUSHVSP

# push the obscured wanted value (value_1)

0x48859c: VFETCH32 [VSP] ([0xffffcfa0] = 0xffffffff -> [VSP])

# NAND the obscured wanted value and the MBA obfuscated compared value

# ~value_1 & ~value_2 = 0x0 & 0x0 = 0x0 = true

# if value_2 is not the intended one, this NAND will return a value great then 0

0x41586e: VNANDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (~0xffffffff & ~0xffffffff = 0x0 & 0x0 = 0x0 -> [VSP])

0x4459ea: VPOPR32 R14 (0x44 -> R14)

# add the "conditional" offset to the jump offset

# add (~value_1 & ~value_2) to jump offset : 0x0 + 0x4522ae

0x43166b: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0x0 + 0x4522ae = 0x4522ae)

0x4187d4: VPOPR32 R1 (0x0 -> R1)

# set R2 to next jump offset : 0x4522ae

0x409350: VPOPR32 R2 (0x4522ae -> R2)

Right after, the swapping jump is done :

# push each registers to swap after jump

0x41d886: VPUSH32 R15 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x46cde8: VPUSH32 R11 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x473217: VPUSH32 R9 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x4300a5: VPUSH32 R3 (0x50384a8 -> [VSP])

0x40fb72: VPUSH32 R10 (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x41470e: VPUSH32 R11 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x482d01: VPUSH32 R6 (0x44 -> [VSP])

0x456732: VPUSH32 R0 (0x50384d4 -> [VSP])

0x442df0: VPUSH32 R4 (0xffffe000 -> [VSP])

0x47c4dc: VPUSH32 R5 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x4778dd: VPUSH32 R15 (0x0 -> [VSP])

# push jump target

0x41d886: VPUSH32 R2 (0x4522ae -> [VSP])

# jump to [VSP], this jump variant only swap VIP (esi -> esi)

# NOTE : in this case it's a useless swap

0x43ab3a: VJUMP_1 [VSP] (0x4522ae + 0x0) (VIP = esi -> esi)

# pop each registers to swap them

0x469ef9: VPOPR32 R3 (0x0 -> R3)

0x4346f1: VPOPR32 R8 (0x0 -> R8)

0x40c7e3: VPOPR32 R2 (0xffffe000 -> R2)

0x474a78: VPOPR32 R14 (0x50384d4 -> R14)

0x450d42: VPOPR32 R15 (0x44 -> R15)

0x4459ea: VPOPR32 R4 (0x0 -> R4)

0x4187d4: VPOPR32 R1 (0xffffcfac -> R1)

0x409856: VPOPR32 R6 (0x50384a8 -> R6)

0x409350: VPOPR32 R13 (0x0 -> R13)

0x464561: VPOPR32 R11 (0x0 -> R11)

0x480d95: VPOPR32 R10 (0x0 -> R10)

And this is the code executed after the jump :

# another junk jump .....

# this is the next opcode executed

# mov dword [ebp-0x4 {var_0}], 0x29a

# push 0x29a (666)

0x47b585: VPUSHI32 0x29a (VSP -= 4)

# calc var_0 stack offset

0x423839: VPUSH32 R9 (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

0x41ca5f: VPUSHI32 0xfffffffc (VSP -= 4)

0x46184e: VADDU32 [VSP], [VSP+0x4] (0xfffffffc + 0xffffcfac = 0xffffcfa8)

0x44538c: VPOPR32 R11 (0x91 -> R11)

# var_0 = [0xffffcfa8] = 0x29a

0x45efdf: VMOV32 VSP[0xffffcfa8], [VSP+0x4] (0x29a -> VSP[0xffffcfa8])

Well again, as the jump condition is melted into MBA, it’s pretty hard to understand what’s going on without lifting.

VIII – Tricks to make things harder

VIII.1 – Outside VMP code

VIII.1.1 – Intruction variants

Some VMP instructions have the same goal, but are different in terms of code (not in terms of code mutation). Here the example of VJUMP, those two are the same, but there behavior are differents, one is swapping VIP into VSP, the other is placing VSP in edi. In fact, there are 4 jumps like that in VMP, and they are a variant of each other.

0x82520d: VJUMP_2: (VIP = ebp, VSP = edi)

0x82520d: mov edx, dword ptr [edi]

0x825212: add edi, 4

0x82521f: xchg edx, edi # swap VIP and VSP using "xchg"

0x899aba: mov ebp, edx

0x7ee22f: mov ebx, edi

0x7ee234: mov edx, 0

0x7ee23f: sub ebx, edx

0x77a6a8: VJUMP_1: (VIP = ebp, VSP = esi)

0x77a6a8: mov eax, dword ptr [esi]

0x77a6aa: add esi, 4

0x77a6b3: mov ebp, eax

0x77a6b7: mov edi, esi # change VSP from esi to edi

0x89a168: mov ebx, ebp

0x89a16a: mov ecx, 0

0x89a16f: sub ebx, ecx

VIII.1.2 – Operand offsets variants

Here is a push immediate instruction in two variants, those two grab the imm with different offsets in opcode. Sometimes the VIP is increased negatively, and sometimes positively.

0x79b54a: VUNKNOWN: (VIP = ebp, VSP = esi)

0x79b54a: mov ecx, dword ptr [ebp] # encrypted imm offset at VIP + 0

0x79b54e: lea ebp, [ebp + 4]

0x79b559: xor ecx, ebx

...

0x871597: xor ebx, ecx

0x87159b: sub esi, 4

0x8715a9: mov dword ptr [esi], ecx

----------------------------------------------------

0x73e3d5: VUNKNOWN: (VIP = esi, VSP = edi)

0x73e3d5: sub esi, 4

0x73e3db: mov eax, dword ptr [esi] # encrypted imm offset at VIP - 4

0x73e3e0: xor eax, ebx

...

0x73e3f8: xor ebx, eax

0x73e400: sub edi, 4

0x73e406: mov dword ptr [edi], eax

VIII.1.3 – VIP and VSP swapping

Like shown in VIII.1.1 - Intruction variants, VMP swaps its VIP and VSP registers randomly during the execution flow.

VJUMP_3 [VSP] (0x48677d + 0x0) (VIP = edi -> esi) (VSP = ebp -> edi)

VJUMP_3 [VSP] (0x42b7bd + 0x0) (VIP = ebp -> ebp) (VSP = esi -> edi)

VJUMP_2 [VSP] (0x427772 + 0x0) (VIP = esi -> ebp) (VSP = ebp -> edi)

VJUMP_2 [VSP] (0x44ecca + 0x0) (VIP = esi -> edi) (VSP = edi -> ebp)

VJUMP_1 [VSP] (0x47e4c3 + 0x0) (VIP = ebp -> esi)

VJUMP_1 [VSP] (0x47a555 + 0x0) (VIP = esi -> edi)

VJUMP_1 [VSP] (0x443595 + 0x0) (VIP = esi -> esi)

VIII.2 – Inside VMP code

VIII.2.1 – VMP registers swapping

As you saw previously, each jump is “swapping” every VMP registers, every register are pushed on the stack, and popped right after in differents registers. In order to complexifty the control flow.

0x41d886: VPUSH32 R15 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x46cde8: VPUSH32 R11 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x473217: VPUSH32 R9 (0x0 -> [VSP])

0x4300a5: VPUSH32 R3 (0x50384a8 -> [VSP])

0x40fb72: VPUSH32 R10 (0xffffcfac -> [VSP])

.....

0x43ab3a: VJUMP_1 [VSP] (0x4522ae + 0x0) (VIP = esi -> esi)

0x469ef9: VPOPR32 R3 (0x0 -> R3)

0x4346f1: VPOPR32 R8 (0x0 -> R8)

0x40c7e3: VPOPR32 R2 (0xffffe000 -> R2)

0x474a78: VPOPR32 R14 (0x50384d4 -> R14)

0x450d42: VPOPR32 R15 (0x44 -> R15)

.....

VIII.2.2 – MBA

VMP pass all its value using randomized MBA, using models like (MBA_XOR_*(x,y) = (MBA_SUB_*(MBA_OR_V*(x,y), (MBA_AND_V*(x,y))))). Here are some I found during my reseach :

x ^ y = (~(~(x) & ~(y)) & ~(~(~(x)) & ~(~(y))))

x ^ y = ((~(~(x)) & ~(~(y))) + (~(~(x)) | ~(~(y))))

x ^ y = ((~(~(y)) | ~(~(x))) + ~(~(x)) - (~(~(x)) & ~(~(~(y)))))

x ^ y = ((~(~(x)) | ~(~(y))) + (~(~(~(x))) | ~(~(y))) - (~(~(~(x)))))

x ^ y = ((~(~(x)) | ~(~(y))) + ~(~(y)) - (~(~(~(x))) & ~(~(y))))

x ^ y = (~(~(y)) + (~(~(x)) & ~(~(~(y)))) + (~(~(x)) & ~(~(y))))

x - y = (~(~(x) + y))

x - y = (~(((~(~(x)) | y) - (~(~(x))))))

x - y = (~((~(x) & ~(x)) + y) & ~((~(x) & ~(x)) + y))

x & y = ((~(~(x)) | y) - (~(~(~(x))) & y) - (~(~(x)) & ~y))

x & y = ((~(~(~(x))) | y) - (~(~(~(x)))))

x | y = ((~(~(x)) & ~(y)) + y)

x | y = (((~(~(x)) & ~(y)) & y) + ((~(~(x)) & ~(y)) | y))

x + y = ((~(~(x)) & ~(~(y))) + (~(~(x)) | ~(~(y))))

...

# NOTE : VMP seems to do addition normaly (without MBA) most of the time

VIII.2.3 – Random ‘calls’

Some times, I see ‘calls’ (VPUSHVSP, VPOPVSP) with no reason, and I can’t figure out if this is real junkcode, or a real separeted stack.

VIII.3 – Ultra mode

Let’s now take the same first example (math one), but in Ultra mode. Our code is now about 20817 instructions, and 428 VMP instructions. There are too much code to cover, so I will just say that the main different is that MBA is way heavier, and there are a lot of VJUMP (registers swapping + VSP/VIP swapping). Also, we have to consider that the original code is mutated, so it add a lot of virtualized instruction to the routine.

IX – Devirtualization

So how could we crack this ? Well we can talk a bit about the ‘Devirtualization’ approach.

IX.1 – The “less proper way” : Pattern matching

The simplest method, get the x86 execution flow in some way (statically or dynamically) is to figure out which block is which VMP instruction by pattern matching (like I did, but for every control flow cases). And once this is done, you can convert it to another language like x86. But the code will be horrible due to the MBA and register swapping, so the most effective choice is to convert it in a compiler optimization language (LLVM, VTIL like in NoVMP). From here you can do code lifting / opt passes to remove junkcode, MBA, and other obfuscations, and the final code could be exported in x86. LLVM passes have been made in the pass multiple times for this purpose, and a lot of implementation simplify the deobfuscations in LLVM IR.

For example, you can just use the default optimizations passes of LLVM to lift your routine output, my friend IDontCode did it to devirtualize VMP 2.x (here) with great results (less MBA on this version tho).

About the MBA, you can translate the routine into SMT and simplify it to remove it, like what Mrphrazer does (see: Code deobfuscation framework to simplify Mixed Boolean-Arithmetic). You can even covert the IR code to SSA expressions to simplify them using Miasm or Triton (a good example here from mrt4ntr4). Even an LLVM optimizer called Souper coded by Google implements an SMT simplifier to optimize LLVM IR.

Jut to mention it, Fvrmatteo devirtualized VMP using C++ templates to LLVM IR, and wrote very good articles on how he lifted the LLVM routines (Tickling VMProtect with LLVM). His LLVM optimization passes are public and could be used to simplify the LLVM output even more. Note that powerfull frameworks exists to lift obfuscated code using LLVM IR, like SATURN (here).

IX.2 – The efficiant way : DTA & Symbolic execution

The much more complicated way… by using Dynamic Taint Analysis or Symbolic execution, the goal will be to understand how the VM deal with its registers to define what the VM does. In short, understand the code from the VM context, to define instructions that produce the same result as the virtualized code. This is not something easy as you may guess, there is an excellent paper of Jonathan Salwan, Sebastien Bardin, and Marie-Laure Potet about this task Symbolic deobfuscation : from virtualized code back to the original

Here are some examples of implemations of this approach :

- Jonathan Salwan made a script (here) about Tigress VM to simplify its routines using Symbolic execution. With Triton symbolic expressions representing the virtualized routine, you can apply a simplifier called Arybo to remove VMP’s MBA very easily and export the result into LLVM IR.

- An other example about taint analysis on a VMP routine (UniTaint). The taint output of the emulation is listed and then compiled as C code, before getting passed through clang with optimization passes to get a lifted simplified output.

- Mrexodia published an example of simplification through symbolic execution on VMP using Triton engine (VMProtectTest).

X – About speed

From my analysis, virtualizing a simple xor takes about ~40 VMP instructions (the instruction is melted with obfu, it doesn’t take 50 instruction to do a simple xor operation). And considering that every handles are mutated (core + next opcode calculation), and the internal VMP opcode could be obfuscated even more in Ultra Mode. A VMP routine could lead to execute ~2000 instructions for a single xor (take this with a grain of salt, it’s my own conclusion based on what I saw).

In my example, 17 instructions were converted in 5943 instructions, and about 126 VMP instructions. And in Ultra mode, those were converted to 20817 instructions, and 428 VMP instructions. I tried to mesure the time difference, but it depends on a lot of factors like CPU type / usage, kernel / resources usage, running processes… So I will stay on the number of executed instructions.

According to throwawaycracker, D***** was about the same rate in 2015 : "an x86 instruction will be translated into about between 2 to 50 VM instructions". And considering that D***** virtualization was based on VMP at the time (like very close to it), I think that my analysis is close to the reality.

XI – What do we do now ?

So I made a debugger for it, based on qilling. Unfortunately, qiling doesn’t support API calls, you have to implement them (understandable). So there are only two possibilities for me, the first is to continue on the easy path (runtime) by coding or modding an x86 emulator for PE that could handle API calls (like ‘unicorn_pe’ but for x86). The second one is to code a static tool (like the first part of NoVmp) using emulation through something like unicorn. But those two are time consuming, and currently I don’t have this time. So I will continue with my debugger that does the job kinda well, and export the VMP opcode into an LLVM routine with some optimization passes. And export the LLVM IR into x86 to a new section in the executable.